The launch of the Rosemarket Local History Society website and the subsequent publicity it generated, came to the attention of a member of the Heath family, who had lived in Rosemarket over seventy years ago.

The parents Harry and Doris, and sons John and Hal (who had been christened William Henry but was known as Harold or Hal), moved into the property that was then known as The Old Vicarage in mid 1951. Then in 1953 daughter Daphne was born, followed in 1958 by a son David. John, who was 14 years old at the time the Heath family moved into The Old Vicarage, was to spend most of his teens there until November 1954 when he left home to study to be an Electrical Engineer in England. In July 1963, the Company he was working for asked to him to go to Australia for three years, and except for two separate periods of one year and two year’s duration, when he worked in California, he has lived there ever since.

John realised after his father had died that he knew very little about his life prior to his marriage. In an attempt to ensure that this would not be the case for his children, John has written his autobiography and has kindly agreed to share some of his recollections of living at The Old Vicarage with us. What follows are extracts from his beautifully written document.

How The Old Vicarage, Rosemarket, became our new home

We were living in one of the new council houses in nearby Waterston in late 1950 and despite it having all the modern facilities Mother hated it. She had grown up on her uncle’s farm in Waterston, and loved tending to all the animals and working with the two farm hands her uncle employed. Her connection with the land came to an abrupt end in 1936 when she married my father, who, at that time, was an officer in the British Merchant Navy. Mother never lost her ‘love for the land’ which led her deciding some years later that she had to find a place where she could again have a few animals to look after.

Her search ended several months later when she found just what she was looking for in The Old Vicarage in Rosemarket and we moved into it in mid 1951.The house had originally been the home of the vicars of Rosemarket, and presumably had been originally called The Vicarage. When the New Vicarage was built sometime prior to WWI, the Vicarage, along with a field of about three acres in area, was sold and became known as The Old Vicarage.

It was an idyllic spot and one of the first things Mother did was to change the name of the property to ‘The Glen’, as it was in a shallow sheltered valley with a crystal clear stream flowing through it. The photograph, which was taken shortly after we moved in, shows The Glen with the much grander New Vicarage to its left. The boundary hedge between the two properties had two gates in it that allowed access between them. A variety of tall trees provided protection from the north and west. The stream was dammed at two places to the left of the photo to form small ponds, and below these the valley was thickly wooded with a wide variety of large and small deciduous trees. The woods stretched from here to Westfield Mill and beyond, and they provided a useful source of wood to eke out the coal we burnt to heat the house. They also gave us a great playground and we spent much of our leisure time playing in them.

The smallholding had a large and productive vegetable garden. It had been cultivated over a great many years, and it’s incredibly fertile soil had enabled the previous owners and later my family to grow an impressive array of vegetables. The field was less fertile with large patches of bracken. It would have benefited greatly from an occasional dressing of lime and fertiliser, but we could not afford to do this.

The Glen had none of the domestic services that were found in most houses – it did not have electricity, gas or piped water, so, as we had done when we lived in nearby Scoveston Fort during the War, we had to rely on an open coal fire or a paraffin-fuelled primus stove for cooking and heating, Tilley lamps for lighting, and on a well, which was about sixty yards from the house, for water. There was one usable out building which was a large tin shed. This was sub-divided to serve as a workshop, store room, cow shed, pig sty and poultry shed, and the only toilet was attached to it. There were also ruins of what we understood had been a coach house and several pigsties but these were in such a dilapidated state to be unusable and even if they were worth rebuilding, we could not afford to have done so.

Access to The Glen was by a narrow unsealed laneway that crossed the top end of the field from the main road. This field is where cricket matches were played in later years. A short branch off the lane provided access to the New Vicarage. The final section as it neared our house was slightly steeper as it descended into the valley, and in rainy periods, which were all too frequent, this fifty yard section became quite slippery and made it difficult for the occasional vehicle that delivered some supply or other to us, to exit the property.

The house was two storied with two large rooms downstairs, each with an open fire, and an annex on the north side, which served as a dairy. Upstairs there were two large and one smaller bedroom, all large enough to accommodate double beds. My parents slept in the largest room and, for some reason, my brother and I slept in a double bed in the smaller one. The other large room was used as a storeroom. Each of the five rooms had a small square window which despite facing south did not admit much light and the rooms were quite dark even when it was a bright sunny day.

The house was built of stone and had a slate roof. Most of the outer walls were approximately two feet thick with the one that formed the west end of the building, about six feet thick. This had two small built-in recesses– a storeroom for fuel for the fire, and a cavity in the chimney just above the grate that was large enough for a person to stand up in, to allow soot to be removed. The stone construction made the surface of the inside walls quite irregular but this did not deter Mother from wanting patterned wallpaper in all of the rooms. It proved impossible to match up the pattern on the adjacent pieces of paper many places and we all dreaded it when Mother decided she wanted a change of wallpaper. I think my strong aversion to decorating any of the homes I have lived in over the years has stemmed from this frustrating but character-building experience.

Our drinking water came from a well fed by a small spring, and the water was always crystal clear and icy cool. One of my regular duties was to fetch two pails of water for use in the house each morning. Surprisingly, we did not appear to have endured any ill effects from a family of water rats that had made it their home throughout the time we lived there. If we were careful enough we could creep up to the well and see them preening themselves – they seemed to be very fussy about their personal cleanliness!

The overflow from the well flowed into the main stream, stretches of which were covered in masses of watercress for much of the summer. My brother and I ate large quantities of this when it was in season, usually having it with chips, eggs, bacon and a variety of salad vegetables from the garden. I recall that the combined flavours of egg yolk, watercress, salt, pepper and vinegar, became one of my favourite taste sensations!

I wasn’t too keen to move

When I first learned we were going to live in Rosemarket I was most put out at the thought of leaving my home in Waterston and my friends in the village. It also meant that I would have to transfer to Haverfordwest Grammar School, as Rosemarket was in that school’s designated service area, and I was not happy about that. I am not sure how it came to be, but I did not have to make the transfer and I finished my secondary education at Milford Haven Grammar.

My brother, who had only just started his secondary education at the same school, would have been less affected by moving to a new school, but he too continued to attend Milford Haven Grammar.

Initially, the only way we could get to school was by cycling to Johnston, leave our bikes at the blacksmith’s shop there, and catch the regular Haverfordwest to Milford Haven bus. We took the route via Troopers Inn despite it being the longest of the three routes we could have taken, as it was slightly less hilly than the other two. The need to cycle to Johnston ceased towards the end of 1952 when a special school bus was introduced to transport children from Rosemarket, Tiers Cross and several outlying farms to the new Secondary School in Haverfordwest. Conveniently, we were able to catch it at the top of our lane and get dropped off at the bus stop in Johnston where we caught the bus to Milford Haven. It provided just as convenient transportation home in the afternoon.

Mother starts to acquire her menagerie

When we first arrived at The Glen, Mother reckoned that the field would produce enough grass to feed a cow, so she bought an in-calf Shorthorn/Ayrshire cross and christened her Arabella. Except for a few months when she had just calved or had stopped lactating, Arabella provided us with enough milk and butter for the several years we had her. Shortly afterwards, Mother bought a Large White sow that she christened Josephine, for breeding, and several geese and chickens for eggs and poultry.

Josephine was a particularly bad tempered pig who took an immediate dislike towards one of the two vicars that resided in The New Vicarage during the time we lived at The Glen. Josephine would froth at the mouth whenever he paid us a visit and we had to put her in her sty whenever he called on us. Josephine had several other bad traits that clearly demonstrated just how dangerous pigs could be. Like all pigs, she had an insatiable appetite and given half a chance would dig up the ground to a depth of two feet or more looking for roots and insects to eat. In a matter of a few days, if allowed to, she could make the field look like an open cut mine! To try to prevent this, we had a ring inserted in her nose, the traditional way to discourage pigs from digging, but in next to no time she would hook the ring over something strong and simply rip it out of her nose. Within a couple of days the wound would have healed sufficiently for her to resume her search for tasty morsels.

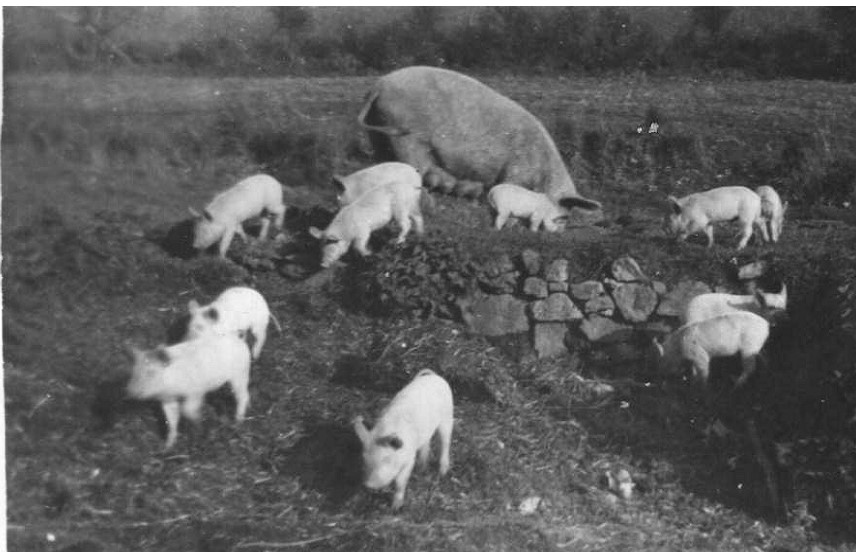

Another sobering demonstration of her strength was when she would vent her anger on a tractor tyre that had been split in half to make a feeding trough, by tearing chunks out of it. She was a good breeding sow however, and she always produced large healthy litters as this photograph of her and one of her litters of eleven piglets shows.

The photograph of Josephine and the other photographs were taken on my first camera, a very basic Agfa box camera.

Billy (the goat) had some bad habits too!

After a couple of years mother was forced to accept that the field could not provide enough feed to support a cow, and as we could not afford to buy in hay or rolled oats to supplement what grass there was during the winter months, we had to sell Arabella. We were very sad to see her go after she had kept us amply supplied with milk and butter. I was glad however that I would no longer have to painstakingly shake cream in a large glass jar for what seemed like an eternity, to make butter. Nor would I have to walk miles around the neighbouring farms looking for her each time she came into heat and felt the call of nature.

In order to ensure we still had an alternative supply of milk, we replaced her with a family of four goats, the male was appropriately named Billy, the nanny was called Minnie and their two young nanny offspring Blacky and Fauny. I never really took to drinking goat’s milk as it had a much stronger taste than cow’s milk and too frequently tasted of the wide range of vegetation they had eaten.

I did however very much enjoy the rich creamy desserts such as custard, blancmange and rice pudding Mother made with it. The photo of Billy and Fauny shows them tucking into what appears to be a pile of discarded broad bean stalks from the vegetable garden.

Billy could be quite a nuisance at times. When he was in a bad mood, which was all too often, he would sneak up behind you, give you a hefty butt with his rather intimidating horns, and if he managed to knock you to the ground, he would stand menacingly over you, ready to give you another butt if you tried to get up. He had several goes at Mother when she was milking one or other of the nannies, and he was foolish enough to do this to my brother and myself on a couple of occasions. He came to realise that this was not such a good idea after we dragged him into the middle of the stream, forced him onto his back with his horns trapped under his body so that he had difficulty in getting to his feet, and leaving him to enjoy a cold bath.

The rest of the menagerie

We later acquired a second fully grown pig, a Wessex Saddle Back, which because of her distinctive colouring, we christened Blackhead. She was an incredibly docile pig and we were able to tickle her about the face and feed her titbits by hand, something we would never attempt to do with Josephine. We also reared turkeys and chickens, and sometimes geese and ducks, for sale locally at Christmas time. The two or three weeks before Christmas were rather busy as we killed, feathered and dressed the birds. They were also a period of frantic scratching because of the poultry mites. We never had any difficulty selling the poultry we reared, as even in those days, free-range poultry was in high demand.

Whilst the animals had no natural enemies, it was a different story with the poultry, and it was always a bit of a battle to ward off the interest of several types of predator. The adult poultry were continually at risk from foxes, and the small chicks, goslings and young turkeys were easy prey to sparrow hawks, buzzards and occasionally, grass snakes.

I try to help out

In an attempt to help financially, and to have a few shillings pocket money, I started a weekend job with my Uncle Ben, who was a butcher. This was delivering meat which I did by bicycle to houses in Waterston and some outlying farms that took about two hours on Friday evenings, and in Neyland, Hazelbeach, Honeyborough, Little Honeyborough and Mastle Bridge that took about seven hours on Saturdays, for which I was paid ten shillings a week.

Uncle Ben had a butcher’s bike, but because it weighed a ton, had only one gear and incredibly poor brakes, I preferred to use my own bike, resting the basket on the handle bars and balancing it between my arms. Throughout the two and a half years I did the round I never failed to turn up for the delivery run, no matter how bad the weather was.

Initially I used the money I earned from the meat round to buy new shoes and clothing, and to go to the cinema in Neyland with several of the other boys in the village on Saturday evenings. Soon after moving to Rosemarket, I started to have problems with the gears on my bike and despite several attempts to fix them they continued to be a problem. They became so bad that I decided to buy a new bike and I spent ages looking over all the glossy brochures I could find, before settling on a Hercules Kestrel that cost just over £21. It had a frame made from Reynolds 531 tubing, which made it one of the lightest and strongest available at the time and was fitted with the latest type of gears – a 3-speed derailleur, which would be considered rather basic by today’s standard of 15 or more speeds! With these three gears however there weren’t too many hills in Pembrokeshire that I could not ride up, and there were plenty with gradients of one in six, and some with short sections that were as steep as one in four. It also had alloy fittings (brakes, mudguards, wheel rims and pump) and I fitted a Miller dynamo to it.

I was very proud of my new bicycle, and it served me well until it was stolen in 1958 when I was a student living in Rugby.

Wilbur joins the family

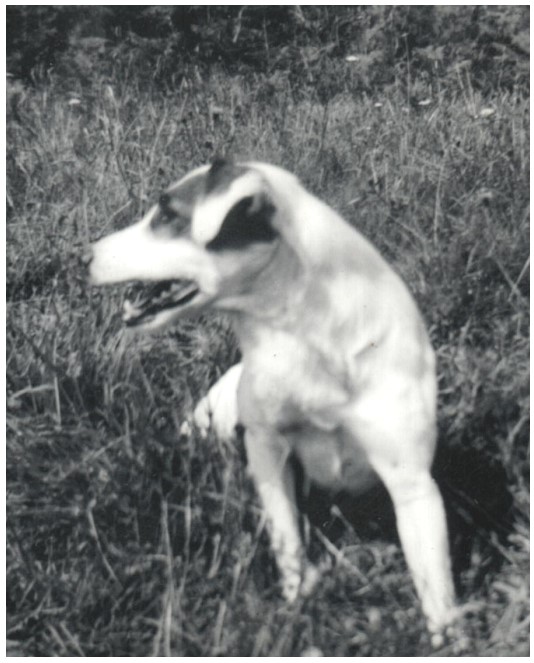

Soon after moving to ‘The Glen’, my brother was given a terrier cross collie pup from the farm at nearby Harroldstone. We duly christened the pup Wilbur after a school friend, who, for some unknown reason, had acquired this nickname. Despite being the runt of the litter, Wilbur grew into a fine dog. He was incredibly strong for his size with the stature, looks, stamina and aggression of the terrier. He invariably won the many fights he had with much larger dogs in the neighbourhood and killed the foxes he encountered from time to time. In fact I do not think he was ever beaten in a fight, even though on one occasion he picked a tough opponent in a badger, and he came home with quite a few wounds for his trouble.

Wilbur was remarkably intelligent, alert and obedient, and when my sister, and later my youngest brother, were small, he took on responsibility for protecting them whenever they were outside. A good example of this was when Billy, the goat, decided he could resume his bad habit of butting people, although now he made sure they were smaller than he was. Daphne was wandering around the field, when Billy decided it was time he showed her who was boss and knocked her over and made her cry. Wilbur was not at all impressed with Billy’s display of bad manners and decided that he had to be discouraged from continuing them by taking a few chunks out of one of his ears. Billy did not bother her again.

Wilbur was also remarkably trustworthy and if we told him not to touch any of the rabbits or poultry we had just killed, or food that was on the table, we knew they were safe. In marked contrast, Trixie, our other dog, would take anything she could eat the moment our backs were turned, and had it not been for Wilbur, she would have made off with quite a few meals. Wilbur also had a remarkably varied taste for a dog - he clearly believed that what was good enough for us to eat when we were out and about - blackberries, hazel nuts, carrots, turnips, etc., were also good enough for him. He would even go ‘fishing’ for elvers in the streams by standing in the shallow water on three legs, and with his other paw, he would stir up the water plants to flush them out into clear water, and add a fish supplement to his diet. We were all saddened when he died quite an old dog after the family had moved to Little Honeyborough and he was run over by a tractor.

You would think we were all little angels

After we moved to Rosemarket, my brother and I, as a result of some gentle persuasion from Mother and the Rev Cecil Percival Willis, our vicar neighbour, attended the village church and joined the Church Youth Club, Cymry’r Groes. Most of the boys and girls in the village and the surrounding farms attended the club which was held each week in the village hall.

My brother and I were confirmed in 1952 and attended Communion and Evensong services most weeks. We were both members of the choir, and I read the lesson and carried the cross in the procession from time to time. I am back row, 2nd from left, and my brother was one of the candle bearers. He is the one on the right.

A very merry vicar

It was a regular tradition in the village at the time for the Church Choir to go carol singing at Christmas time to raise money for the church. This was done on foot around the village, and, thankfully, on the back of a lorry to reach the outlying farms, as some of them were some distance from the village.

It was invariably an enjoyable experience for all involved, as at each farm, young and old alike, were given a generous serve of whatever alcohol the farmer had. This was more often than not, some very potent home brewed concoction and by the end of the evening we would all be in very high spirits.

Some unintended consequences

Many of the houses in the area had a problem with jackdaws, in that their preferred nesting place was any chimney that was not in use. The farmhouse at Westfield Farm was one of the largest in the area with several chimneys that had become nesting places for the pests. As we were keen collectors of bird’s eggs we asked the owner if he would like us to remove the jackdaw’s eggs. With his agreement, we climbed up a tree adjacent to the house and onto the roof and then made our way to the first of the two chimneys. We succeeded in removing most of the eggs with a bent spoon attached to a long stick but there was one nest that was just beyond the reach of our makeshift tool.

We concluded that the only thing we could do to make this nesting site unattractive to the jackdaws was to drop one of the loose stones we found on the top of the chimney on to the eggs and break them. It became all too evident that this had not been such a good idea at all, when we heard an angry shout followed by a stream of threats to our well being. We glanced down and there was a very angry owner making us aware that the stone had crashed through the nest and released a cloud of soot into one of the downstairs rooms, and he wanted us to know that he was far from amused. He disappeared still making threatening noises and before we could climb down and scamper away he reappeared with his four-ten shotgun and pointed it in the air. As we scurried to the opposite side of the roof to get down, there was a loud bang and a shower of shredded leaves fluttered gently down onto us.

This convinced us to make ourselves scarce with much greater urgency. We climbed into the overhanging tree and scrambled to the ground just as he appeared around the corner of the house. There was another loud bang and a second lot of leaves fluttered down onto us. Although it seemed at the time that he was acting with deadly intent, we later gave him the benefit of the doubt by deciding he had taken care to aim well above our heads!

An attractive alternative

The family’s poor financial state meant that we could not afford a traditional Christmas tree with all the usual decorations so we had to make do with a holly one instead. Holly trees were to be found in reasonable numbers throughout the woods and hedgerows, and they made a very attractive substitute with their glossy green leaves and bright scarlet berries.

We end up with a very burnt offering

During the summer school holidays, we would often spend the whole day in the woods building dens and playing cowboys & indians, hide & seek or relievio (a variation of tag). We usually ‘lived off the land’ on these occasions eating anything we found that we knew to be edible.

On one particular day though, we decided we would like something different for lunch, and after discussing the limited number of options available to us we settled on chicken, which we intended cooking over a fire in the woods. We decided that a particular farmer was going to kindly donate one of his chickens, and after a rather noisy chase we managed to catch one.

We hastily moved to a remote part of the woods and set about feathering and preparing the chicken before threading it on to a stick and cooking it over a small fire. We cooked the chicken for what we thought was enough time, and as it was beginning to look a bit like a large cinder, we eagerly set about dividing it up.

You can well imagine how disappointed we were when we found that despite its charred appearance it was almost raw underneath, and our much-anticipated feast was confined to a few bits and pieces that had the appearance and unappealing taste of lumps of charcoal!

As soon as we reached school we set off for home

The winter at the start of 1953 was very cold with one quite heavy fall of snow that was sufficient to close most of the local roads to traffic. This included the one my brother and I used to travel to school on so we eagerly looked forward to a day off school. Unfortunately Father had other ideas. The route he took to get to work was clear and as he set off for work he informed us that he expected us to go to school. As the only way we were going to get to school that day was to walk there we set off by the most direct route via nearby Jordanston and Steynton for our nearly four and a half miles walk to school.

It took us about two hours trudging through two feet or more of snow for most of the way. We arrived at school about 11am, wet through and freezing cold from the knees down, only to find that all lessons had been cancelled because many pupils, some of whom lived only a few hundred yards from the school, and also some of the teachers, had not bothered to turn up. Those teachers, who had made it to school admired our devotion to learning, but suggested that we should dry ourselves out as best we could, have lunch and immediately set off on the return leg. We arrived back home at about 3.30pm. As the weather conditions were no better the following morning, we at least had that day off!

A silly thing to do

Two school friends visited me at The Glen during the summer holidays in 1953 and we went down to what is officially called Westfield Pill but known to us as Westfield Mill, because of the ruins of a water mill on its shore. It was in the stream feeding the mill that I caught the only fish I ever caught by ‘tickling’ it. The boys in the village used to try to catch the numerous small trout that were in the local streams by ‘tickling’ them with varying degrees of success. The fish I caught was a sewin, which is also known as a sea trout. It was over a pound in weight, which made an enjoyable meal, so I was well pleased with my one and only success.

Westfield Mill was a picturesque spot. The sides of the tidal valley were covered in woods with the occasional clearing that was covered in bracken and bluebells. The area was home to a variety of birds including buzzards, rooks, crows and the occasional jay, and animals such as squirrels, foxes and badgers. Swans and other water birds inhabited the tidal areas. The railway line from Neyland to Johnston, and eventually Cardiff and London, ran along the western side of the inlet. Sadly, this section of the rail network, along with many others throughout the United Kingdom, was closed following the Beeching Review of the British Rail Network in the 1960s, and the track was subsequently removed.

Part of the route we used to take to get to Westfield Mill followed the railway line for about half a mile. One of the pranks we played from time to time was to place a coin or other small object on the line to have it flattened by an engine. On the way home after this particular visit, we decided to go one better, placing a long line of small stones spaced every few yards apart on one of the lines. We reached the point where we needed to leave the railway line when we heard a train approaching and one my friends, who had not participated in the exercise up to this point, thought that he would make up for his previous non-involvement by putting a single somewhat larger stone on the other line.

As the train approached we noticed the engine driver peering intently out of the side of the cabin at the line where we had placed the small stones. Then the train ran over the larger stone on the other track and screeched to a halt.

We rapidly decided that this was another of those occasions when we should immediately make ourselves scarce. We scattered in all directions; I made my way back to the village shop, quickly entered it, bought an ice cream, and, leaning casually against a wall outside the shop, proceeded to eat it as slowly as I could. A few minutes later a red-faced railway man rode up on a bicycle and enquired of the shop owner, the customers and me, if we had seen any boys running up the road, which none of us had. I finished my ice cream and then walked home. The others eventually arrived back at the house covered in mud after having taken a rather circuitous route through the woods to avoid the village.

The birth of my sister Daphne

Mother became pregnant for the third time in late 1952, which was a bit of a surprise for everyone, as Mother was 38 at the time, and Father was 51 and his health had already started to fail. I suppose really, as a 15 year old, I was rather embarrassed about it initially, but I was thrilled when my sister, who was christened Daphne Florence, was born on 26 July 1953.

Her mishaps with the geese

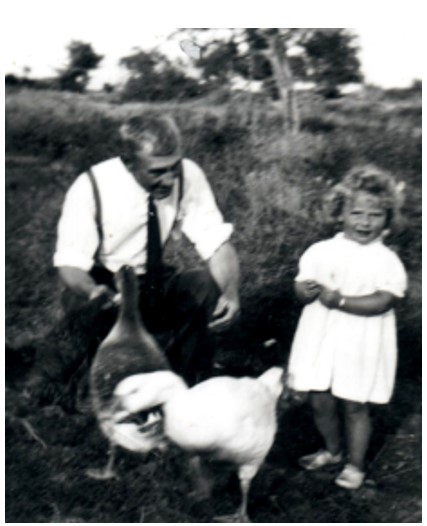

Daphne, like Mother, loved to be with the animals and despite several unpleasant incidents with them from time to time, had no fear of any of them. In this photo she is with Father and the gander and goose we kept so that we could raise several broods to sell at Christmas time. Goose was quite popular at this time, and although nowadays it has almost totally disappeared with the almost universal choice of turkey for Christmas lunch, I still consider a goose to be the best table bird for Christmas.

On one of my trips home I noticed the gander, the white one in the photo, had part of his upper beak missing. He could be a bit of a nuisance at times, particularly when he felt it was necessary to impress his girlfriends. His favourite tactic was to come up behind you without you being aware of his presence and give you a rather painful peck somewhere on the rear.

Apparently he had done this once too often to Daphne, and had made her cry. When Mother heard her cry she dashed out to see Wilbur proceeding to set about the gander, and by the time he was satisfied that the gander had been appropriately punished, Wilbur had bitten a large piece of the top half of the gander’s beak off. It was as though Wilbur knew that by biting off part of his beak, he would not be able to peck Daphne again.

Mother was concerned that with a part of his beak missing, the gander would not be able to eat enough to survive and she thought he should end up on the dinner table. She decided to wait a few days before administering this fate to see if he could still eat, and despite his injury he learned to eat remarkably well, and never attacked Daphne or anyone else again.

Daphne was to have another rather sad mishap with the geese sometime later. She used to love playing with all the young animals Mother reared, which she treated as her toys. On this occasion, Mother had let the goose sit on two eggs which had hatched out. Daphne was thrilled with the little goslings and for a while, they became her favourite pets. She used to take them instead of her doll for rides in her pram.

One day, Mother heard her sobbing that Bertie and Beryl, as she had christened them, could not stand up anymore. When Mother went to investigate, she found Daphne trying to get them to stand up but their legs kept buckling and Mother concluded that Daphne in covering them up to keep them warm, had unfortunately suffocated both goslings.

Despite having these and the other unfortunate experiences she had with the various animals, some of which were quite painful, Daphne, much like Mother, maintained a love of animals and after she left school she worked as a veterinary assistant for many years.

My brother David

Mother became pregnant again in early 1958. Understandably, this came as an even bigger surprise to everyone than the time she became pregnant with my sister five years earlier, as Father was now 56 and she was 44. She gave birth to her third son on the 24th of September 1958 and christened him David Morgan. Mother and baby fared very well considering Mother's age.

I did not get to see him until I went home nearly three months later for Christmas and found Mother and baby in good health. Daphne was delighted to have a baby brother and she looked after him with great enthusiasm.

I took this picture when I went home to The Glen the following Easter, by which time he was about six months old. The ever-faithful Wilbur as usual is in the picture, as he never ventured far from Daphne or David whenever they were outside.

Goodbye to The Glen

The impact of Father’s deteriorating health and the arrival of brother David had made it increasingly difficult for Mother to continue at The Glen, and so, early in 1961, they moved into a small bungalow in Little Honeyborough. It was only slightly more luxurious than The Glen in that it had electricity and cold running water but still did not have hot water, a flushing toilet or a bathroom, so it was still a rather spartan existence for the family.

Father’s breathing difficulties, which started after he fell off a crane during the war and broke several ribs exacerbated by a lifetime of heavy smoking became progressively worse as he aged and he died of emphysema in 1969 at the age of 68, leaving Mother to fend for two school-age children.

Daphne and David survived the hardships of growing up without a father for much of their youth, and I am immensely proud that both attended Milford Haven Grammar, an achievement that can be attributed to the considerable personal sacrifices Mother, and to a lesser extent Father, made over many years. I very much regret that by the time I was in a position to repay them in some small way for all those sacrifices, Father had died and it was quite late in Mother’s lifetime.

Nowadays, almost seventy years after I left my Rosemarket home in November 1954 to pursue a career in engineering I often recall the character building influences The Glen had on all of the Heath family. Despite all the hardships we had to endure living there, it was a great place to grow up in and I still recall, somewhat nostalgically, how much I used to enjoy listening to the sound of rain lashing against the windows, as it all too frequently did, and the wind in the trees when we were tucked up snugly in bed; the smell of new mown hay from nearby fields wafting through the open windows in the late summer evenings, and the baying of the dog foxes and the hooting of the owls on moonlight nights.

It certainly helped prepare me for what has proved to be an eventful, interesting and rewarding life with its many enjoyable highlights far outweighing its few disappointments.

CLICK HERE to read about and watch John Heath's talk at the first public meeting of Rosemarket Local History Society on 5th September 2023.